Black Hair Day

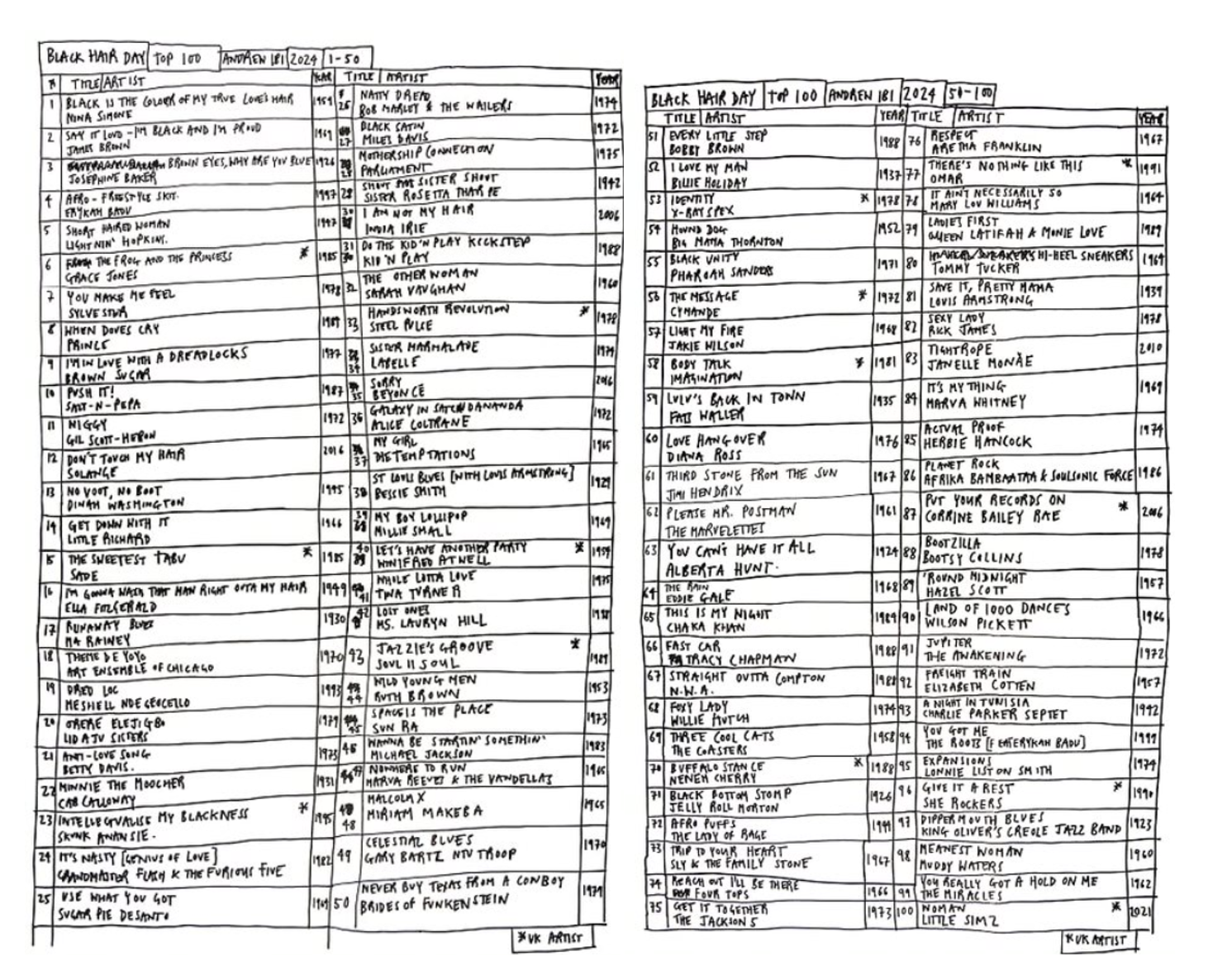

Andrew Ibi: Top 100 Black hair songs for the Horniman Playlist.

The intrinsic link between music, style and fashion is illustrated graphically throughout the history of Black hair, often documenting a shift in cultural, political and societal values. Sadly, we have to endure the trauma of slavery in order to honestly debate and understand the importance of Black hair politics and their place in modern society.

The role of Black hair in music has served to pacify, monetise, popularise and even, antagonise throughout the ages and along the way, it’s symbolism of strength, freedom, courage, rebellion, resistance and power has been forged through every instrumental note played, every vocal note sung or rapped and every complex composition recorded.

The role of Black hair in music has served to pacify, monetise, popularise and even, antagonise throughout the ages

Given that the central position and global perspective of beauty extended through colonialism, it is no wonder that afro-textured hair was destined for politicisation. Since the hierarchy of hair texture supported a racial caste system, Black people began to adapt, inadvertently accepting European, imposed beauty standards - firstly for survival and then for economic and social progress.

From the invention of modern Black music to present day, Black artists, performers and musicians have navigated decades of political turmoil – often with their hair at centre stage.

Since the hierarchy of hair texture supported a racial caste system, Black people began to adapt, inadvertently accepting European, imposed beauty standards - firstly for survival and then for economic and social progress

Part 1: Save it, Pretty Mama

With the popularity of Black music escalating at the turn of the twentieth century, it was the invention of Blues and Jazz that elevated Black musicians to the forefront of music culture and with it, the politics and etiquette of the day. The 1920’s was known as the Jazz Age and Black musicians began to migrate towards the mainstream through live performances, film and audio recording.

The practice of hot combing and chemical straightening became common place and with it, the promise of respectability, economical ascension and positive social status. These enforced cultural values were captured in the early and developmental stages of Black music, with both male and female performers and artists like Josephine Baker, Jelly Roll Morton, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway either chemically altering - ‘conking’ their hair, or in the case of Smith and Rainey, the adoption of horsehair wigs.

Many lyrics from this period express detailed descriptions of Black hair texture, with strong conventional, gender narratives being played out through innuendo.

Part 2: No Voot, No Boot

As early Blues and Jazz music matured into mainstream listening in the 1930’s and 1940’s, the musician’s role was generally to provide respite, entertainment and to offer a sense of collective self-reflection. It was common for female artists to comment on their own appearances and grooming regimes – including graphic descriptions of hair and beauty. In contrast, their male counterparts were conditioned to pass judgement or ridicule the appearance of women’s hair. Lightnin’ Hopkins famously penned ‘Short Haired Woman’ in 1947 – a song lamenting that short hair is equal to trouble.

The significant cultural uptake of the conk hairstyle, also referred to as ‘good hair’, helped with the complex assimilation of Black identities to broader, white audiences and the public. Black artists were now able to access the music industry, ultimately performing an acceptable version of Black culture tailored for white audiences. The simulation of European hair was becoming a potent weapon used for economic progress.

Artists like Billie Holiday and Dinah Washington broke commercial ground, their appearances helping to make them appear respectable to wider audiences.

The simulation of European hair was becoming a potent weapon used for economic progress

Part 3: Black is the Colour

With hair at the forefront of musical evolution, it was the rise of Rock and Roll during the early 1950’s which nurtured a new type of artist and musician. Influenced by their predecessors, but even more theatrical in style and performance, virtuosos including Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, led a new tone of Black music and alongside their flamboyant performances and racy lyrics was an associated, new sartorial elegance embellished with exuberant hair styles. Little Richard was as well-known for his radical image as his music, his six-inch quiff progressively growing through the 1950’s.

There was, however, one woman who challenged the cultural normative behaviour of the day and laid the foundations for a politically charged career. Nina Simone recorded her version of ‘Black is the Colour of My True Love’s Hair’ in 1959, a stand-alone anthem of self-reflection and one of the first recorded songs to affirm and openly proclaim, Black pride, Black identity and self-love.

‘Black is the Colour of My True Love’s Hair’ in 1959, a stand-alone anthem of self-reflection and one of the first recorded songs to affirm and openly proclaim, Black pride, Black identity and self-love

Britain in the 1950’s saw the supremely talented Winifred Atwell record and release a number of commercial records with huge success. In 1956, Atwell became the first Black person to have a number one hit and she was also the first Black artist in Britain to sell a million records. In the same year, Atwell opened her Brixton hair salon, intrinsically linking her own musical brilliance and style with her hair choices. Throughout her career, her hair styles played an important role, moving through chemical processing to wigs and natural styles later on in her career. Atwell was an icon of her time and often missing from conversations regarding Black British artists.

Part 4: Respect

The 1960’s was largely recognised as a pivotal moment in modern Black history, ushering in a convergence of youth, new ideas, new political figures and new musical masterminds. The birth and meteoric rise of Motown in 1959 and throughout the 1960’s consolidated a new era of music for the masses. The Black, all-women music band emerged, with Marva Reeves and The Vandellas, The Marvelettes and Diana Ross and the Supremes taking centre stage as new popular performers. However, their presence was still derivative of western beauty standards, albeit with a sassy flourish, the music was delightful, sentimental and entertaining, their hair styles concur with heartfelt storytelling and their projected, soft demeanours.

The early 1960’s recorded a slow transformation in the hairstyles worn by Black male musicians and by the mid 1960’s there was a change of political tone in sound and performance, with artists leaving behind the Rock and Roll hairstyles and attitude of Little Richard, Jackie Wilson and their peers.

Motown’s prominence was now established and in 1964, The Temptations recorded ‘My Girl’, an enchanting ballad representative of the time, but by 1970 their song, ‘Psychedelic Shack’ had a new, revolutionary freedom sound, with the band in possession of a new radical image.

Part 5: Say It Loud

Born in 1933, Barnwell, South Carolina, James Brown’s musical prominence in the late 1950’s responded directly to the changing face of Black America and its political terrain.

The assassination of Malcom X in 1965 coincided with Brown’s style transformation as he assumed the position of an established icon, social figure, political activist and leader. Brown was now synonymous with the Black Civil Rights Movement, his music swerving away from love songs in search of new freedom sounds. A decade that oversaw the transformation of sweet soul, rotated fully into illicit funk, and culminated in 1969 as Brown recorded the Black power anthem, ‘Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)’. During the same year, Marva Whitney adopted the Blonde Afro hairstyle and released, ‘It’s My Thing’ with equally powerful vocals and a forceful stage presence. In the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, Brown and Whitney’s adopted Afro hairstyles, in place of yesterday’s looks, signified a seismic shift in political values for the masses, an allegiance with the Black Panther party, and the definition of a new era of Black, political struggle and consciousness.

Motown’s political transformation was complete with the hitmakers releasing Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going on’ in 1971 and the Jackson 5 breaking the international mainstream with the Afro hairstyle. This meant rejecting the names and identities established through slavery - and subsequently, oppression and racism. The Afro hairstyle was a perfect symbol of defiance and identity.

Motown’s political transformation was complete with the hitmakers releasing Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going on’ in 1971 and the Jackson 5 breaking the international mainstream with the Afro hairstyle

“I been sleeping all my life. And now that Mr Garvey done woke me up, I’m gon’ stay woke. And I’m gon’ help him wake up other black folk.” This was Barry Beckham’s seminal line in his play, ‘Garvey Lives!’. It was a moment which perfectly illustrated changing times, where Black people rebelled, Beckham had unwittingly invented the modern definition of ‘woke’.

As Black music shifted from compliance to defiance and with African Americans mobilising to seek ‘knowledge of self’ from external sources, and with global events like apartheid in full view, Africa came into focus.

‘Mama Africa’ or Miriam Makeba, had a profound impact on the adoption of natural hair by African-American women in the US. Miriam’s ‘Khawuleza (Hurry, Mama, Hurry)’ was released in 1965 and captured the events of apartheid South Africa and police township raids. Children would shout, ‘Khawuleza Mama’ - don’t let them catch you.

The revoking of Makeba’s passport by the South African Government, granted a new, powerful international profile and her distinct style and look was imitated, "I see other black women imitate my style, which is no style at all, but just letting our hair be itself. They call it the Afro Look."

Marrying African-American civil rights activist and Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael in 1968, further consummated a union of revolutionary struggle.

The early 1970’s was a hotbed of cultural and creative energy with Blaxploitation movies adding cinematic action to style and music, their graphic illustrations of the Afro hairstyle becoming a vivid statement of conscious progress for both men and women. In 1973, Pam Grier was ‘Coffy’, a moment celebrated with a soundtrack by Roy Ayers, and in 1974 we met ‘Foxy Brown’. This powerful new imagery disobeyed the submissive visual stories and narratives of Black women in the 1950’s and early 1960’s, with the ballads and love songs transitioning to content centred on women’s perspectives, their sexuality, politics, class and race.

With the Revolution in full swing, Gil Scott-Heron released ‘Wiggy’ in 1972, a poem which provided a strong, conscious perspective, but retrospectively felt heavy handed having somewhat dismissed cultural patriarchal perspectives and values. Nonetheless, the central commentary reflected on disbanding with European notions of beauty. It’s interesting to note the style evolution of Miles Davis, having had a career spanning three decades to this point, he also adopted the radical freedom and celebratory style of the day.

With the Revolution in full swing, Gil Scott-Heron released ‘Wiggy’ in 1972, a poem which provided a strong, conscious perspective

As Black culture forged new global alliances, new style and musical genres evolved. Reggae’s global prominence was being shaped by an influx of R&B artist’s sounds to post-war Jamaica and by the late 1950’s sound systems were born. Ska music dominated the 1960’s with its slick emulation of Motown, and amongst its early pioneers were a young band called, The Wailers, and its front man, future global superstar and icon, Bob Marley.

Marley’s conversion to Rastafarianism in the late 1960’s positioned him with an unapologetic approach to freedom, having adopted the rebellion and resilience of dreadlocks which centred him at the forefront of revolution. Black hair was destined to leave an indelible mark on all future style subcultures.

British Reggae bands such as Steel Pulse and Aswad, sprang out of the late 1970’s having adopted the style of Jamaican Rastafarianism and on the other hand, The Lovers Rock scene was dominated by softer, more sensual sounds and spearheaded by Black Sugar and vocalists, Janet Kay and Carol Thompson. Their natural approach to hair, beauty and style was revealed through their music and cultural, lyrical reflections.

The influence of Black music from the US played a huge part in the development of the Black British sound. Bands like Cymande and The Real Thing reflected the emotional struggle of Black people globally ,whilst artists like Maxine Nightingale sang songs that were designed and shaped to make communities feel good.

Part 6: Eboness

As a period of spiritual, cultural and emotional reclamation ensued, the free jazz and spiritual movement of the mid 1960’s erupted and sustained a charge into 1970’s as an open conversation with Africa. A legacy of John Coltrane’s masterpiece, ‘A Love Supreme’, the consolidation of radical new Black identities manifested; Pharoah Sanders, The Ensemble Al-Salaam, Black Renaissance, The Descendants of Mike and Phoebe, Alice Coltrane, and Sun Ra & June Tyson.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago were centre stage in the spiritual jazz movement and released the cult classic, ‘Theme de Yoyo’ in 1969. Combining classical free jazz elements with deconstructed funk structures and gritty vocals, the track is a rare synthesis of Black identity in all of its complex guises. The band’s garb, stage presence and performance denoted a direct ode to Africa, with the conscious and deliberate erosion of European and western style.

The band’s garb, stage presence and performance denoted a direct ode to Africa, with the conscious and deliberate erosion of European and western style.

Part 7: Mothership Connection

Sun-Ra, who is largely regarded as the pioneer of ‘Afro-Futurism’ through his intergalactic associations starting in the 1950’s and 1960’s, recorded ‘Space is the Place’ in 1972. His work built on his assertion that he was from Saturn and illustrating the principles of Afro-Futurism - Freedom & Movement, History, Mysticism, Egyptology, Science Fiction, and Technology. Needless to say, Ra abandoned all traditional concepts and approaches to traditional western style and dress codes, donning outrageous headwear in lieu of hairstyles during for pursuit of his intergalactic space travelling voyages.

The Mothership Connection and the continuation of Afro-Futurist practice confirmed Parliament and Funkadelic’s most popular musical period between the years of 1975 and 1980, with George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, Sly Stone and the influence of Jimi Hendrix at the helm. Otherworldly performances required more creative approaches to dress codes, style, apparent gender and hair attitudes and as the 1970’s braved new territories, the strict uniform of the 1968 revolution rescinded and the Afro hairstyle took on a more playful tool of value.

Betty Davis performed using extraordinary stage wear and costume performance to subvert traditional narratives of Black women, embracing Black power, feminism and an Afro-Futurist theatre.

Non-binary approaches, apparent gender fluidity and overt sexual exhibitionism radicalised Black hair further. Artists like, The Brides of Funkenstein and Betty Davis performed using extraordinary stage wear and costume performance to subvert traditional narratives of Black women, embracing Black power, feminism and an Afro-Futurist theatre.

Part 8: I Feel Love

As soul and funk evolved through the 1970’s - Disco was born. It was a music less constricted by heteronormative gender standards and constructs, including the role of traditional sexuality. It was also a more racially diverse scene and with new freedoms, came new approaches to Black hair and performance. If the 60’s was a decade of self-proclamation and cultural affirmation, the 70’s was a decade of further cultural, identity examination and exuberant embellishment.

Patti Labelle and the Bluebelles rebranded from doowop and ballads to radicalise their style and art direction with edgier, harder and more exhilarating performances. Their stage presence and afro-futurist costumes were accessorised by new hair standards and changing, community values – these were not the nice, friendly hairstyles of the 1950’s and early 1960’s.

The musical shift and new sexual revolution are clearly marked by the sixteen-minute, 1975 studio production of Donna Summer’s, ‘Love To Love You Baby’ – and radically changed the perception of Black women with mainstream audiences – Summer’s hair was a perfect accomplice for a sexually charged performance. Like many Black Women artists of the period, Diana Ross, re-emerged as a successful solo artist to eventually join the disco revolution. Ross adopted the freedom and style that the new sound promised and delivered a move away from her girl group shackles and perfectly coiffed hair.

Music opportunity was no longer monolithic for Black artists and Sylvester’s era defining and ground breaking track, ‘You Make Me Feel’, further challenged limited identities of Black bodies and sexuality. His global and iconic presence as a Black, queer male challenged the perception of mainstream Black masculinity and beauty. A wide range of make-up and hairstyles were used to subvert Black music and image further from the industry’s, constructed conservatism of earlier decades.

Music opportunity was no longer monolithic for Black artists and Sylvester’s era defining and ground breaking track, ‘You Make Me Feel’, further challenged limited identities of Black bodies and sexuality.

Grace Jones released her first three albums in the late 1970’s. As much a fashion icon as a musician, Jones’ powerful presence was always topped off by an extraordinary fade cut - sometimes tapered, sometimes asymmetric or sometimes with a high top. Her complex identity and performances challenging stereotypes of Black woman – it was probable that her hair was a reference point for the first women of Hip-Hop during the mid 1980’s.

Chapter 9: Push-It

If Reggae, specifically Ska, is beholden to Motown and the US, it could be said that Hip-Hop owes a debt of gratitude to Reggae. Sound system culture’s impact on the early Hip-Hop pioneers as early as 1973 was an enabler for the music genre’s growth and evolution.

Early Hip-Hop style, predating its name, was a hybrid of street culture and Disco sensibility - harnessing theatrical, over the top, immoderate and excessive stage clothes - or costumes. There was more than a nod to Afro-Futurist sentiments that can be traced through the lineage of P-Funk right back to Sun-Ra. Hair was no passenger, and young Black men were not resistant to the theatre of the 1970’s. Early images of Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five illustrate the impact of Disco on their sartorial choices, with the Jheri Curl making its rap debut.

Even NWA were not impervious to the Jheri Curl’s charms with Ice Cube and Easy E recorded as early adopters nearly a decade later.

Was the Jheri Curl the magical ingredient that allowed global icons like Michael Jackson and Prince to maximise their undoubted talents into superstardom? Was the 1980’s a remix of the decades that preceded the 1960’s? The softening of the Black image through relaxed hair statements allowing for more palatable celebrity and audience crossover.

Black image through relaxed hair statements allowing for more palatable celebrity and audience crossover

Hip-Hop was now well into its second decade, having moved away from the fiction of stage costume to a new, but complex, gritty street identity. The male dominated genre saw the first women of rap systemically emerge during the mid 1980’s, and with it, new radical ways of defying traditional Black hair values - another youth rebellion was consecrated.

Salt n Pepa offered a new, alternate narrative and reality to young Black women, and their hair play was a vehicle of mass dissemination. Pepa’s signature asymmetric cut was in fact designed by a hairdressing accident. For men, the ‘Flat Top’ and ‘High Top’ fade hair styles also made their first appearances - with Kid, from Kid ‘N’ Play’s standing at around ten inches.

In Britain, bands and performers including Lynx, Imagination, Loose Ends, Sade and Jaki Graham mirror the international style of their Black counterparts and adopted similar hair styles and beauty politics of the time. Sade was particularly coveted for her style, her slicked hair allowing her to achieve race ambiguity and giving her a platform to crossover commercially.

The uptake of Hip-Hop in Britain was also a key moment in the development of Black music, with a positive self-determinism at its core. The She Rockers and Moni Love expressed their music through their visual identities. Moni Love’s ‘Ladies First’ performed with Queen Latifah, was an empowering feminist anthem commenting on gender politics and its relativity to Black women - spotlighting hair and beauty was inescapable.

Part 10: Don’t Touch My Hair

As Hip-Hop looked for new cultural perspectives, authority and relevance to impress and reassert traditional Black values of pride and identity - the ‘keeping it real’ mantra materialised. Dreadlocks and The Afro, made their way back into Hip-Hop culture - Lauryn Hill and Busta Rhymes were early adopters. Questlove’s Afro, adorned with Afro Comb, framed The Roots mission statement, delivering introspective storytelling and picking up identity politics forged in the late 1960’s and 1970’s that had been scattered through later decades.

There was a deep connectivity to the politics of Funk and Jazz music and the late 1960’s Civil Rights Movement, with James Brown’s music frequently being sampled and restored to the frontline and Gil Scott-Heron illuminated as the Godfather of Rap.

Black hair was now a complex assemblage of decades worth of styles, politics, economics, perceptions and cultural values.

The early 1990’s gave rise to the foundations of the Neo-Soul movement, a perfect stable mate for the golden age of Hip-Hop. It was an alternative to the more commercial ‘New Jack Swing’ sound which was performed by artists like Bobby Brown. Brown’s high intensity dance music was supplemented by appropriate dress codes and daring new hair styles. The ‘slanted’ Gumby would come to epitomise the entire genre and generation.

The ‘slanted’ Gumby would come to epitomise the entire genre and generation.

In Britain, the late 1980’s oversaw the arrival of new Black British identities into the mainstream with Neneh Cherry’s career flourishing and intrinsically linked to Fashion’s Buffalo movement – hair being a major factor in its distinctive visuals. But it was Soul II Soul and Jazzie B, along with Caron Wheeler, who galvanised a Black, British identity forging cultural heritage with new Black experiences and future aspirations. A new adaption of dreadlocks gave birth to ‘The Funki Dred’, with Omar Lye-Fook, and The Young Disciples consolidating the movements permanence.

The freedom of the 1990’s Britain allowed new and distinct voices to surface, less limited by race and cultural expectation - but nonetheless, still strained by historical structures. Skin, lead singer of Skunk Anansie, had a forceful presence and steely image - her shaven head a symbol of rebellion and liberty.

In 1997, Erykah Badu released ‘Baduizm’, and was sat at the helm of the genre along with Jill Scott and Lauryn Hill. Black women were central to the movement with their lyrics challenging and interrogating stereotypes, patriarchal perspectives, cultural tropes and provided self-affirmation and positivity. The reclamation of natural hair was not only seen, but often became content for song writing.

A new adaption of dreadlocks gave birth to ‘The Funki Dred’, with Omar Lye-Fook, and The Young Disciples consolidating the movements permanence.

Solange, India Arie, Lady of Rage, Meshell Ndegeocello and Kelly Rowland all penned or performed songs titled with references to Black hair. Hair was no longer part of the visual display or a line or two in a song, it was now the defining structure – embedded into song writing and storytelling.

Released in 2016, Beyoncé’s ‘Sorry’ famously declared; ‘He only want me when I'm not there, He better call Becky with the good hair.’

A reference that takes us all the way back to the 1920’s and the emulation of European hair standards. What did she mean?

Yesterday’s musicians and artists have skilfully manufactured a cultural legacy rich in creativity, freedom and identity. By blending heritage, with new experiences - Black identity has been woven into the fabric of underground and popular music.

Today’s recipients reflect proudly and confidently, speaking freely and opening about beauty standards, belonging, race, sexuality and gender - hair being an intersectional conversation point. From a British perspective, The Sons of Kemet’s ‘My Queen Is Angela Davis’ evokes vivid historical and political images in our minds whilst Little Simz and Cleo Soul’s ‘Woman’ is testament to progress - a true celebration of international Black beauty in all of its wonderful guises.

Today’s recipients reflect proudly and confidently, speaking freely and opening about beauty standards, belonging, race, sexuality and gender - hair being an intersectional conversation point.